B ethel College (KS) Pride Week Convocation: April 11, 201

ethel College (KS) Pride Week Convocation: April 11, 201

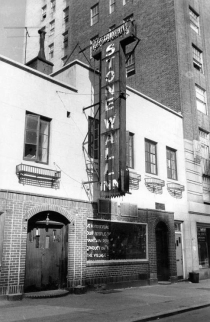

On June 28, 1969, as police were filing patrons out of a gay bar in Greenwich Village, New York, something historical and monumental happened. Usually when the police conducted raids of gay bars, they checked IDs, arrested those who didn’t have them, occasionally committed acts of brutality and the patrons of the bar would go home. But that June evening in 1969, preceded by several decades of consciousness raising, organizing and quiet forms of resistance, people didn’t simply go home. They stayed outside and formed a sizable crowd, until the energy was high enough and a sense of community palpable, and fought back. The patrons of this bar, the Stonewall Inn, reflected the diversity of what was then called the “gay” community, butch lesbians, trans people, drag queens, gay men, all from varied class and racial backgrounds. The following year, activists at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations proposed with a resolution that they move the “Annual Reminder” celebrations that took place on July 4 to “remind” gay people of their inherent worth as citizens to late June to commemorate Stonewall and rename it to Christopher Street Liberation Day. Today, Christopher Street Liberation Day, now known as “Pride,” is celebrated around the world every year in June.[1]

The word “pride” itself comes from late Old English and had cognates in several Scandinavian languages. Interestingly, most Indo-European languages today do not distinguish between a good or bad sense of pride, but in those languages that do, the bad sense seems to have come into use first. Some historians theorize that pride meaning “the state of having a high opinion of oneself,” reflects the Anglo Saxon’s opinion of the Norman Knights who called themselves “proud.”[2] Historically, the term has been associated as one of the seven deadly sins, reflecting the old Biblical notion that “pride comes before fall.” Its association with a group of lions is related to this history because European medieval artists often used lions as symbols for the sin of pride.[3]

During the first Pride Week, thousands of activists in New York “marched up Sixth Avenue from Sheridan Square in Greenwich Village to the Sheep Meadow in Central Park for a ‘Gay-In’ to celebrate the Stonewall anniversary.”[4] Among the crowd, people shouted slogans such as “Say it loud, gay is proud!” and “gay is good.” This public proclamation of pride was an act of resistance against a history of shame.

The term shame also has an interesting etymology and history. The word most likely comes from a pre-Germanic word that meant “to cover.” The Oxford English Dictionary records that this likely reflects the belief that “‘covering oneself’ [is] the natural expression of shame.”[5] In those terms, then, pride can reflect “uncovering oneself,” stepping out from that which veils us, maligns us, and isolates us.

Expressions of lgbtq pride throughout the last half century have been complicated, artistic, both inclusive and exclusive, a reflection of intracommunity issues, and most importantly, necessary. While we recognize what we have inherited from those who came before us, we can learn to express pride in ways that honor multiple truths and realities. Today I’m going to explore a few of these expressions: self-determination and self-naming, building community, and social and artistic expression.

Self-determination and naming has been a vital part of shaping expressions of lgbtq pride. The terms homosexual and transsexual both originated in clinical settings and are linked to the pathologizing of lgbtq people. Before Stonewall, activists attempted to popularize the term “homophile” as an alternative to homosexual. This term was used to signal being part of a social group rather than having a deviant sexuality. Leading up to and after Stonewall, “gay” began to replace “homophile.” Both these terms are self-referential and take the power of naming back from those who have maligned gay people. The term transgender has a similar history. In her 1994 book Transgender Nation, Gordene Olga MacKenzie described the term as “self-generated and not medically applied and [not] a term of disempowerment.”[6] The term transsexual has been used as a form of violence against trans people, reducing them to their sexual organs. Transgender, on the other hand, originated inside of the communities it describes, about twenty-five years after transsexual was coined.[7]

These collective acts of renaming were and continue to be an important place to uncover our truest selves. While the terminology will likely continue to evolve and change as we evolve and change as a community, what is important is that we are using language rather than language being used against us. What we commit to when we name ourselves is the radical act of knowing ourselves, contrary to what shame has told us about who we are. In Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility, author Michael Bronski states of early gay activists, “They recreated themselves as people they chose to be, not people they were told they had to be.”[8]

In Mennonite contexts, I have seen this in my peers who have come out, both in large, public ways and in more quiet, private ways. We have inherited the work of those Mennonites who came out forty, fifty years ago, in much more hostile environments. That act of naming has laid the foundation for my generation and the generations after us to name ourselves publicly. Of course, this history is complicated and there have been countless before us who have been unable to name themselves. When I think of my personal history, I recognize both sides of this. I never came out in the evangelical church I grew up in; I left before I ever came to this knowledge of myself.

And then I came out my sophomore year at Goshen College in the newspaper. I have come to see my leaving and my public coming out both as expressions of pride. In the former, I turned away from the shame I inherited in church; and in the latter, I affirmed who I am as a lesbian. Affirming my identity publicly made me accountable to the label I claimed; it required that I live authentically, to uncover myself while making room for others to do the same.

In recognizing that we are all at different points in this process of naming ourselves, we can also recognize expressions of pride can reflect both communal and unique identities. As lgbtq activists in the mid-twentieth century developed a sense of pride, they also developed a communal identity. In 1970, the apartment of Vernita Gray, a member of Chicago Gay Liberation, became a sort of “early center,” for the lgbtq community in Chicago. Because her number was easy to remember (it spelled out FBI-LIST), when Gay Liberation advertised events and meetings, they included her number and name on the flyers and posters. Eventually, people called at all hours of the night, whenever they needed to and many asked for a place to stay because they were homeless after coming out. Gray offered her apartment as a place to stay, as well as place to hold meetings for Chicago Gay Liberation. Because Gray was able to offer her name publicly, it allowed lgbtq people in Chicago to create a community.[9]

Communal identity as an expression of pride has had many iterations throughout history. An activist who was emblematic of creating community in the name of pride was Brenda Howard, a bisexual rights activist who is often called the “Mother of Pride.” Howard organized the first Christopher Street Liberation Day, with prior experience organizing in the anti-war and feminist movements.[10] According to activist Fred Sargeant, the march a year following Stonewall “indicated a change in strategy for the movement.” He stated, “Leaders promoted silent vigils and polite pickets such as the Annual Reminder in Philadelphia. Since 1965, a small, polite group of gays and lesbians had been picketing outside Liberty Hall. The walk would occur in silence. Required dress on men was jackets and ties; for women, only dresses. We were supposed to be unthreatening.”[11] This shift represented a movement away from “respectable” modes of activism to those that reflected the diversity of the lgbtq community. This was an important shift especially for gender nonconforming and trans people. Howard’s activism and community organizing opened up space for a wider range of lgbtq people to express pride.

A facet of Howard’s activism included co-founding the New York Bisexual Network in 1988, which was a central communication hub for several different bisexual rights organizations. She was also “part of the core group of bi delegates who actively lobbied and educated gay and lesbian delegates from around the country who successfully got bisexual into the title of the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation.”[12] Her commitment to combating biphobia specifically, was a mark of her own pride: she “uncovered” herself in order for other bisexual people to come out and to challenge hostile environments that made coming out difficult. Other community organizing efforts that fostered expressions of pride for specific parts of the lgbtq community include the founding of the Dyke March by the Lesbian Avengers in 1993 and the Trans March, which first began in 2004. Howard’s legacy is one that paid attention to nuance and specificity in a way that allowed more members of the lgbtq community to resist shame and build community.

In Mennonite communities, we can probably identify our “Brenda Howards” on our campuses, at our churches, at convention and in other contexts. Pink Menno and Brethren Mennonite Council for LGBT Interests function in that capacity in many ways, as do lgbtq advocacy groups and support groups on college campuses. In his book about Germantown Mennonite, An Increase in Time, author Richard Lichty states of Martin Rock, the founder of BMC, “His call to gather in mutual support was received by lesbian and gay people as a welcome respite from overt rejection and from the subtle ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ mood in other areas of society and some churches.”[13]

At Goshen, I found surrounding myself with other lgbtq people allowed me to understand ways I could express pride. This past January, I attended a workshop on trauma and resilience for organizers. One of the facilitators, Ricardo Levins Morales, stated that shame is the idea that we have colluded with our own oppression. Community and the consciousness raising that accompanies it, allows us to reject that idea

As I learned from my peers about their experiences in Mennonite churches growing up, I was able to see all the ways that oppression is institutional, rather than the result of personal failures. Many of my friends in Prism, the lgbtq support group at Goshen, also allowed me to understand that my “personal failures” do not include my being a lesbian. Resistance to oppression includes community building and organizing, and from there uncovering ourselves from shame is possible.

Mennonite churches such as Germantown Mennonite Church and Inter-Mennonite Church of South Calgary, that committed early on to full welcome of lgbtq people are also an important form of community building for lgbtq people and our allies. The community offered to lgbtq people in these churches was and continues to be a means by which lgbtq people live into our faith as lgbtq people and not in spite of our identities.

In a 1992 issue of Dialogue, BMC’s old newsletter, Joe Miller, of Germantown Mennonite Church stated, “It is hoped that…through being open and unapologetic about its position, Germantown Mennonite Church will continue to be a shining example for the inclusion of all oppressed groups within the Anabaptist tradition.”[14] It is precisely that unapologetic position that allows lgbtq people in Mennonite spaces to uncover ourselves from the structures that have forced us to veil ourselves.

As lgbtq activists in the twentieth century organized their communities, social and artistic expressions of pride proliferated. In Culture Clash, Michael Bronski details the founding of dozens of publishing houses and publications specifically for the lgbtq community. He states, “It was the development of a lesbian and gay liberation movement which opened the floodgates and allowed the founding of print media run by and for the gay community.”[15] These first publications were not without their problems, but they marked an important shift: the development of a shared lgbtq culture and identity. This shared identity became and continues to be an important aspect of expressing pride.

Without images and reflections of ourselves, we cannot understand who we are, we cannot know our truest selves. Bronski articulates, “Read any number of coming out stories and you will discover that many gay men and lesbians first identified their sexual feelings and desires after reading something about homosexuality.”[16]

The summer following my first year of college, I lived in Denver with my family and was becoming increasingly involved in Denver’s slam poetry community. There were several lesbian and queer female poets who were touring and stopped in Denver. I still remember the night I heard one woman read a love poem about another woman and what I felt in my body, the way the gears started turning in my head. It was one of the first times I heard a positive expression of an lgbtq identity and one that I immediately identified with. Her expression of pride, as simple and as quiet as it was, allowed me to come to a greater understanding of myself, to move away from shame.

It also created space for me to express my identity as a lesbian in my own poetry. Bronski articulates the process of lgbtq artistic expression, “Pain accompanies ostracism and prejudice, but its expression has style and conveys integrity, self-worth and a determination that transforms self-pity into personal strength.”[17] In the contexts I grew up in, I was not given permission to express this aspect of myself and the work of these poets granted me that permission. Shame distanced me from my truest self and poetry has brought me closer to it.

Social expression, both in community and in my romantic life, also brings me closer to myself. Historically, for social and legal reasons, lgbtq people have not been able to have a public social and romantic life. In an oral history video, Vernita Gray, the Chicago Gay Liberation activist I mentioned earlier, stated that people in gay bars could not dance together because someone would shine a flashlight on them and they would be kicked out of the bar. To work their way around this, a member of Chicago Gay Liberation who was a student at the University of Chicago, organized a gay dance at Pierce Tower on campus.

Over 200 people showed up to the dance. Gray explained, “To be able to go to a dance where we could dance together and be openly gay at that time was an incredible experience, it was exhilarating.”[18] The creativity of these activists in using what resources were available to them, and carving spaces for themselves in a hostile environment makes me proud to be a part of the lgbtq community and aware of our resilience. The necessity of transforming hostile environments is also made apparent to me in Gray’s recounting of this history; lgbtq pride has been borne out of a response to the oppression, violence and shaming against lgbtq people.

In Mennonite spaces, lgbtq people and our allies have used social and artistic expression in varying ways to respond to the shame we have inherited from institutions that have been set up against our truths. Pink Menno’s witness of hymn singing strikes me as an artistic expression of pride and as a reclamation of spiritual practices that have been used against us. At Goshen, the Open Letter movement to change the discriminatory hiring policy used many different artistic witnesses as activism. My senior year, Open Letter activists made 1000 purple cranes to represent each of the signers of the letter and placed them in the Church Chapel. This artistic and collective act made visible all those who advocated for a change in a policy that forced lgbtq people to hide themselves.

At the Kansas City convention last summer, the silent witness following the passage of the membership guidelines resolution by Pink Menno was, for me, one of the most powerful social expressions of pride I’ve experienced. Often our bodies are made invisible to those who attempt to shame us, but by placing our bodies directly in their sight, we affirmed ourselves, we unveiled ourselves. The complexity present in moments of pride like the silent witness and in other moments such as hymn singing is interesting to note as well. In this, we can recognize that expressions of pride can be both quiet and loud, that binaries have no place here, that we are both/and, rather than either/or, that there is room for multiple and multi-faceted expressions of who we are.

Returning to the dictionary definition of the term pride, the Oxford English Dictionary defines the term as, “A consciousness of what befits, is due to, or is worthy of oneself or one’s position.”[19] As lgbtq people have come to understand our position in society throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, we have also come to understand that our oppression is not worthy of us, that the shame that veils us is not what befits us. The ways lgbtq people have expressed pride, or our coming to know our truest selves despite what we are told about ourselves, are as vast and varied as lgbtq people are.

Pride can, in many ways, reflect both the uncovering of ourselves as individuals and communities and the uncovering of institutional oppression and shame. I invite the community of Bethel College to carve out spaces for different expressions of pride. In what ways can your school not just include lgbtq people, but affirm them? Where can lgbtq people find reflections of themselves on Bethel’s campus? In what ways does Bethel as an institution offer spaces where lgbtq people can uncover themselves? Where is more space needed? What would it look like for lgbtq people to be unveiled, to live in honor of their truest selves on this campus? What support can your school offer to counteract the legacy of shame? What artistic and social expressions are yet to be seen, heard and valued? As you enter this week, I invite you to make these spaces and think about how to sustain them after this week is over.

My senior year of high school, I was talking to a school counselor about an experience I had earlier that year with another classmate. As I finished my explanation, he told me that what I had experienced was emotional trauma. I can’t recall what I said to him, but I remember feeling surprised. No one had ever framed my story that way. That word, “trauma,” framed the experience in a way that allowed me to understand the weight of it, that it wasn’t just “high school girl drama,” as I had been told it was by my peers and by the media. Through this processing with the counselor, I was able to realize that my reaction to this emotional trauma wasn’t overreacting but a complicated interplay of psychological and physiological reactions that are common for trauma survivors. It became clear to me, just in that simple reframing, that trauma took on many forms and that it affected much more of my life than I had ever been able to name. In the following years in college, I was able to expand my understanding of my own trauma and the ways that the church inflicted spiritual, psychological and emotional trauma on me. These realizations were not wounding in and of themselves, but the repression of all the trauma I had experienced up until that point was beginning to unravel. At times this felt like a previously broken bone responding to a change in atmospheric pressure, but more constant, more persistent.

My senior year of high school, I was talking to a school counselor about an experience I had earlier that year with another classmate. As I finished my explanation, he told me that what I had experienced was emotional trauma. I can’t recall what I said to him, but I remember feeling surprised. No one had ever framed my story that way. That word, “trauma,” framed the experience in a way that allowed me to understand the weight of it, that it wasn’t just “high school girl drama,” as I had been told it was by my peers and by the media. Through this processing with the counselor, I was able to realize that my reaction to this emotional trauma wasn’t overreacting but a complicated interplay of psychological and physiological reactions that are common for trauma survivors. It became clear to me, just in that simple reframing, that trauma took on many forms and that it affected much more of my life than I had ever been able to name. In the following years in college, I was able to expand my understanding of my own trauma and the ways that the church inflicted spiritual, psychological and emotional trauma on me. These realizations were not wounding in and of themselves, but the repression of all the trauma I had experienced up until that point was beginning to unravel. At times this felt like a previously broken bone responding to a change in atmospheric pressure, but more constant, more persistent. When the trailer for the Hollywood-produced movie “Stonewall” was released this past August, activists on the internet took to dismantling the narrative the trailer presented. Featured at the center obf the historic narrative is fictional Danny Winters, a white gay man who moved to New York from Indiana after being kicked out of his home. The trailer depicts Danny throwing a brick through the windows of what is supposed to be the Stonewall Inn and galvanizing the crowd, framing him as the “hero” of the historic Stonewall riots. In a Guardian article, producer Roland Emmerich was quoted saying, “‘You have to understand one thing: I didn’t make this movie only for gay people, I made it also for straight people,’ he said. ‘I kind of found out, in the testing process, that actually, for straight people, [Danny] is a very easy in. Danny’s very straight-acting. He gets mistreated because of that. [Straight audiences] can feel for him.’”

When the trailer for the Hollywood-produced movie “Stonewall” was released this past August, activists on the internet took to dismantling the narrative the trailer presented. Featured at the center obf the historic narrative is fictional Danny Winters, a white gay man who moved to New York from Indiana after being kicked out of his home. The trailer depicts Danny throwing a brick through the windows of what is supposed to be the Stonewall Inn and galvanizing the crowd, framing him as the “hero” of the historic Stonewall riots. In a Guardian article, producer Roland Emmerich was quoted saying, “‘You have to understand one thing: I didn’t make this movie only for gay people, I made it also for straight people,’ he said. ‘I kind of found out, in the testing process, that actually, for straight people, [Danny] is a very easy in. Danny’s very straight-acting. He gets mistreated because of that. [Straight audiences] can feel for him.’”